This post is a message of gratitude to the thousands of kibbutzniks in the State of Israel, written by a former kibbutz volunteer.

When you began welcoming volunteers to your bucolic kibbutzim in the 1960s, you thought you’d kugeled two birds with one stone. First, you could introduce Israel to Jews from the Diaspora communities, especially given the sudden uptick in interest after the Six-Day War. You’d also found a source of cheap labor to pick your fruit, tend to your babies/cows/turkeys, prep your food in the community dining halls, and spend eight hours at a whack rescuing tiny cans of orange juice when they tipped over on the juice factory assembly line.

But after a few years, the demographic of the volunteers shifted, and along with it, the driving motivation behind them coming to your community collectives. Non-Jewish visitors weren’t interested in studying Hebrew and supporting the kibbutzim model. No. The goyim wanted to party.

This created friction. Kibbutzniks disliked when the volunteers’ living quarters turned into fraternity houses. You weren’t happy when bonfires burned too high and noise levels peaked at one a.m. (On my kibbutz, neither were the turkeys: many of them had heart attacks.) You did not enjoy having to resuscitate alcohol-poisoned youth, and cringed if your own children became entangled with volunteers. You worried that inevitably, one of those foreign jackasses would start a fire and burn down a building from cooking toast on space heaters in their rooms.

Rightly so.

On behalf of a moderate percentage of the roughly 400,000 young people who have volunteered on kibbutzim over the past half century, I’d like to offer an apology. And, perhaps, a bit of an explanation.

Using the volunteer section of my own kibbutz as a representative sample, I can tell you this: we came to Israel to seek adventure, and often, to run away from something else. Splintered families. Dead-end job prospects. Uncertainty over career paths. Boredom. Heartbreak. Adulthood.

Imagine our delight when we arrived at a kibbutz, met the other volunteers, and realized we’d just joined our own special kind of mixed-breed tribe. There was safety in our cohort. We could speak up, act out and fuck off, and in at least two dozen languages. We spent our stipends on chocolate, cigarettes and alcohol, and when the latter’s supply in the kibbutz shop ran out (or was tactically suspended), we made covert connections with Yemeni laborers in a nearby village and took our business there. We worked all day, and at night, blew off enough steam to run power-plant turbines. We erased memories, and struggled to form new ones, given our inebriated states.

There were other things going on, too. Sharing of cultures and perspectives. Learning how to navigate a new country. Trying new things (I changed my first diaper on a kibbutz). Making friendships. Growing up. It was messy at times, but it happened.

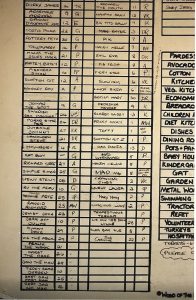

This is where the gratitude comes in, because it was you, dear kibbutzniks, who created this opportunity. You gave us (shitty single) beds, fed us delicious (high-fat) food and washed our (crusty) clothes. You riskily invited us to your family-friendly celebrations. You organized trips around the country for us, to places like Masada and the Sea of Galilee. You dispensed medicine, and sometimes, advice. You taught us how to milk cows, drive tractors, raise children and chop cucumbers into very thin slices.

We couldn’t have had all of that at home. We couldn’t have had all of that anywhere else.

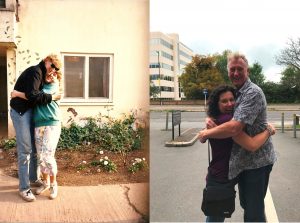

The impact of the things we absorbed during our volunteer tenures was less tangible and visible than what you saw on a day-to-day basis, so I can understand your skepticism. It only just snapped into clear view for me last September in London, when I gathered with a group of eleven volunteers from my former kibbutz, Givat Haim Ihud.

We came together from Canada and the U.S., England and Scotland, Denmark and the Netherlands. It had been 30 years since we last woke to the persistent call of Boker Tov, the volunteer tasked with getting our drunk asses up for work battling a constant game of musical rooms.

Good news: we’ve evolved into stand-up human beings! Informed by our kibbutz experiences, we went on to figure out our families, find our vocational calling (or at least something legal that pays the bills), and feed our hearts. We’re a beautiful lot, and I dare say, we wouldn’t have turned out this great if it weren’t for having stumbled down a few dusty paths together during our time in your country.

Our reunion comprised a whirlwind of a weekend where we tried to catch up on everything and had to say le’hitra’ot too soon. We went through reams of photos and stories from the old days, laughing over the absurdity of our antics. We were so comfortable together, because, after 30 years of trying to explain our kibbutz time to others who just couldn’t get it, we were finally among people who did.

So, thank you, kibbutzniks. All of you. Thank you for tolerating us. We’re sorry for puking in the flower beds. We love what you gave to us, and we’ll never forget it.